The shape of change

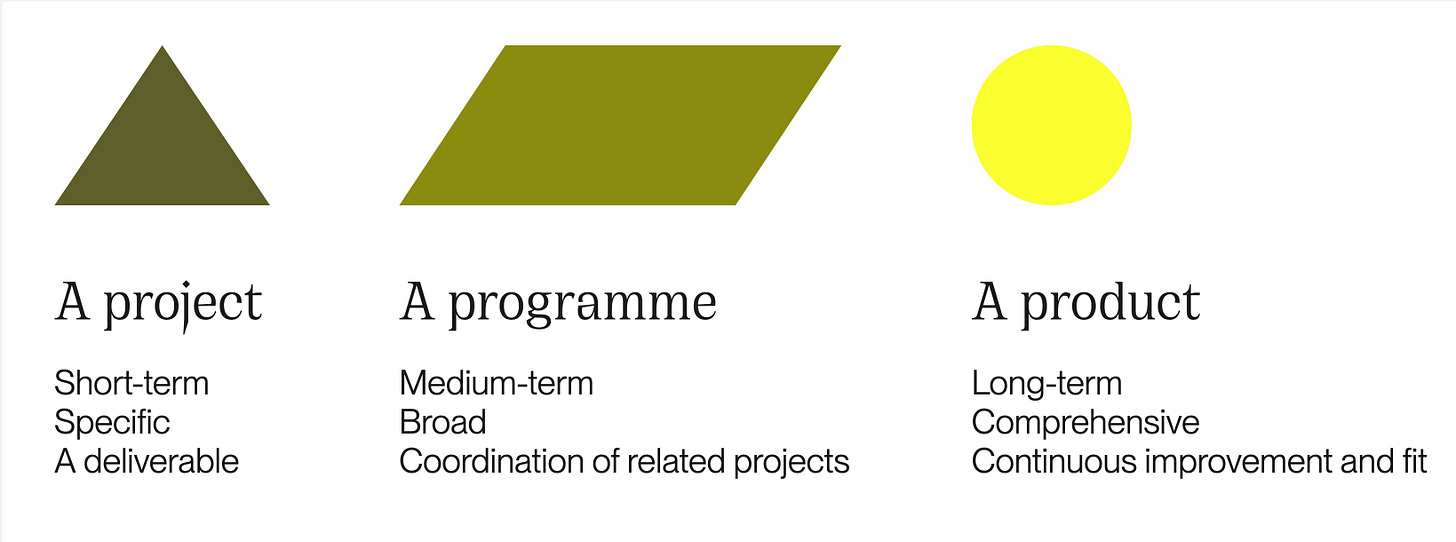

When delivering improvements to large, complex public services, we tend to reduce them to the type of change we're working on: a project, programme or product we’re procuring or building.

When we talk about “delivery,” this is often what we mean: our internal shape for getting things done to a scope, a cost, a result.

We’re less likely to talk about service delivery or how our work adds up to an ongoing outcome for the public.

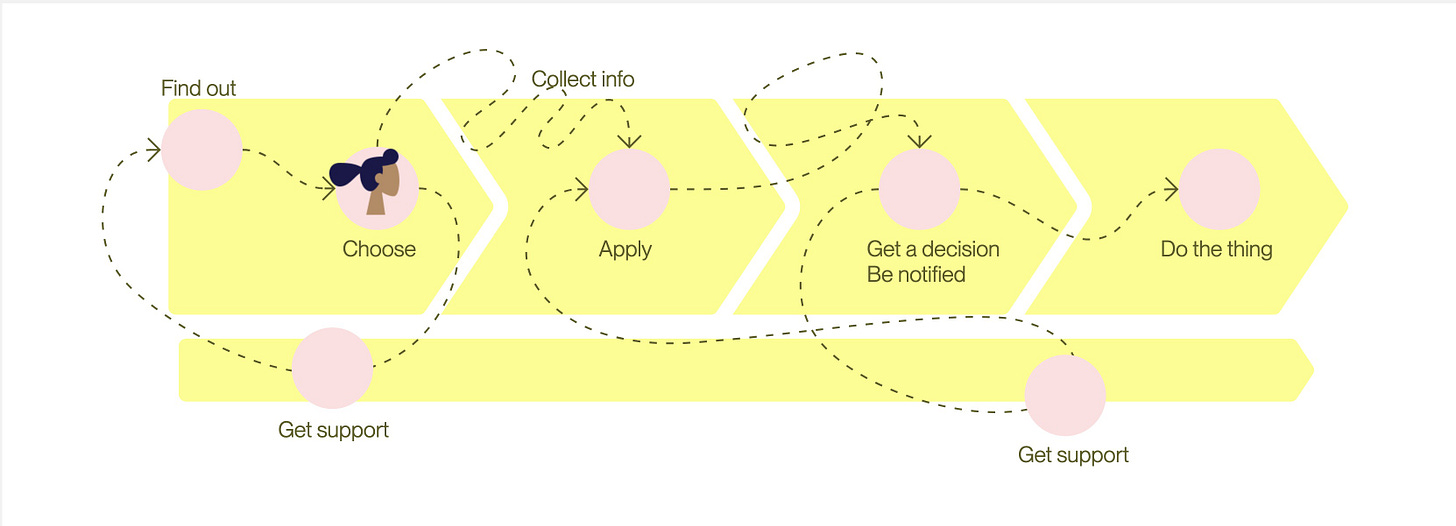

By public services I mean a) something someone needs to do, that b) government has an organisational intent about, like permission to go somewhere or do something, for example.

As long as the public need endures, so will some kind of government response to it. Likewise, the response will shape public need and behaviour. We might even see spin-off services, for example using brokers for driving tests or visa appointments to speed up waiting times.

How people actually use a service rarely figures in delivery outcomes. It’s assumed that whatever makes a public organisation run more efficiently must ultimately benefit the public, even there’s no shortage of evidence to the contrary.

We end up internally focussed, obsessed with how to “deliver change” and “transform” our organisation instead of how to deliver better services.

Measuring delivery vs health

Enduring needs and service outcomes give us a horizon against which to measure improvement, regardless of how it’s delivered or funded.

Just as you never reach a horizon, healthy services are never done delivering. They are ongoing, reacting, changing, evolving. Just like the people, products and platforms that make them up.

Different parts of a service measure many things in isolation to know if they’re operating as expected. For example: a casework function looks at workflow efficiency, a delivery team uses DORA metrics to identify bottlenecks, a data team collects disparate data sets to produce custom reports for policymakers.

Service health is about how these come together and what they add up to. It's more holistic than performance. It includes how well various parts are running, but also how they relate to each other and how responsive to change they are.

Considering service health

Health implies a living system, made up of the actual people and teams involved. Whatever we measure should ultimately help us answer:

1. How well is the service meeting its purpose? For whom?

2. How operationally able are we to able to fulfil that purpose?

3. How capable are the tools and solutions we use to do so?

4. How able are we to improve continuously and respond effectively to change?

Of course, we need to start with outcomes: what we would expect to see for our service and organisation if we were doing well at each level.

For each question, we can look at a) indicators that let us know how we’re doing and b) who is impacted and involved.

Bringing people back into the picture helps to ‘unflatten’ abstract views and identify key relationships. It points us back to the terrain after mapping useful connections.

I’ll explore what these indicators might look like in my next post.

—

Relevant reads:

Jennifer Pahlka on Project vs Product Funding

Kate Tarling on Service Outcomes and Measurement

I’m currently in a delivery space so this is relatable and timely. The closer we get to the end of our public beta and into a national rollout, the more fall into the trap of prioritising business processes over user needs. Your article has given me the a-ha moment for the risk register - we’re at risk of launching an unhealthy service. Thanks for launching a series of articles on this - looking forward to the next one!