The Service Health Check: A Four-Question Approach

See what’s really happening in your service - and how to make it work better for everyone involved

In my last post, I shared how internally focused, programme-led changes are disconnected from actual service delivery.

We measure success against project scope and timelines. But public services don’t stop and start on delivery cycles: they run continuously. How well they’re running right now should be the starting point for any change.

That’s what service health is about. Not just performance, but how the moving parts of delivery - people, policy, operations, and tools - come together to fulfil a purpose.

Here’s a structured set of questions to explore service health. The questions that follow help uncover:

What’s happening in a service: what’s being done, how, and with what outcomes

Who’s involved in making that happen: across users, operational teams, delivery staff, policymakers, analysts, and suppliers

Each section includes both indicators (to assess how the service is functioning) and people (who shape, deliver or are affected by those functions).

Because improving a service doesn’t just mean tracking activity. It means understanding who is doing the work, who’s affected, and who needs to be in the room to make change real.

1. How well is the service meeting its purpose? For whom?

Public service purpose tends to endure. People will still need to apply for permits, file taxes, or receive benefits. The service is how they do that, end to end.

Service health here means understanding the relationship between what people are actually doing and what we expect them to do.

📊 Indicators:

Fulfilment: How correctly and easily users can complete what’s required

Cost and support: Volumes, types of support needed, what it costs to serve different user groups

Differentiate enduring goals (e.g. compliance or fairness) from short-term strategic ones (e.g. response to new pressure)

🙋🏽♀️ People:

Service users, segmented by needs or rule types (e.g. citizens, migrants, low digital literacy)

Policy teams, who define what “success” means and what constraints apply

🧭 Example:

A benefits service sees an increase in incomplete applications from newly eligible groups. While the policy intent is inclusive, the real-world steps aren’t working for everyone. Understanding who’s struggling and why helps teams adjust communications, forms, or rules to better meet the service purpose for that group.

2. How operationally able are we to able to fulfil that purpose?

Service outcomes are only realised through real work: decisions made, cases assessed, complaints resolved.

Health here is about operational capability. Not just what gets done, but how well it adds up to the intended outcome.

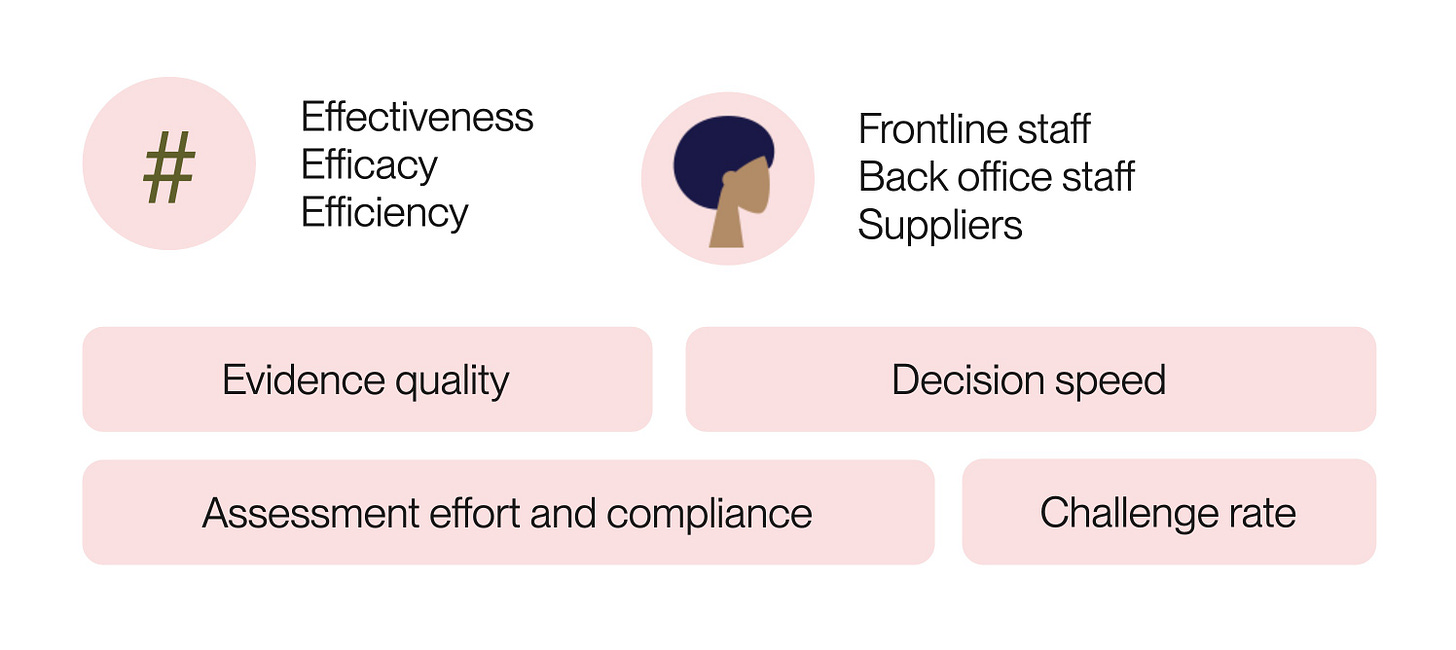

📊 Indicators:

Effectiveness: Are we doing the right tasks in the right order?

Efficiency: How quickly, clearly, and confidently are we working? At what cost?

Focus on the real jobs that need doing, not just job titles or processes. (e.g. “verify eligibility, assess suitability, decide result and restriction” rather than “casework.”)

🙋♀️ People:

Operational staff, both frontline and back office

Suppliers, such as contact centres or system support partners who deliver key parts of the experience

🧭 Example:

In a permitting service, assessors are consistently escalating cases that should be straightforward. A review shows overlapping criteria across processes and unclear guidance. By mapping what staff are actually doing - versus what the process assumes - they can streamline decisions and reduce unnecessary hand-offs.

3. How capable are the tools and solutions used to run our services?

This includes user-facing products, staff tools, shared platforms, and data infrastructure.

Health here means understanding how these systems support - or block - key outcomes and real-world jobs.

📊 Indicators:

Product fit: Adoption, ease of use, usefulness for frontline tasks

Technical performance: Downtime, issues, speed of resolution

Data integrity: Accuracy, reliability, ease of access, sharing, and security

🙋♀️ People:

Product and delivery teams, platform owners, vendors

Policy and regulatory staff, especially for data governance or compliance

Subject matter experts who help shape requirements and solutions

🧭 Example:

A content editor tool for frontline staff is slow, error-prone, and has no autosave. Staff are creating content in Word and pasting it in, leading to formatting errors and missed metadata.

Identifying this workaround helps make the case for investing in better tooling that has the dual goal of being able to implement policy changes in the service more quickly.

4. How able are we to continuously improve and respond effectively to change?

This is about how we respond to feedback, surface opportunities, and act on them. Not in isolated projects, but as part of the continuous work of running and maintaining a live service.

📊 Indicators:

Signal detection: Can we access, interpret, and act on data from live operations?

Responsiveness: How easily can we coordinate and implement a response?

Change delivery: Time to implement, strength of feedback loops, ability to see impact

🙋♀️ People:

Improvement isn’t the job of a single team. It depends on how well we connect the right perspectives across four key areas:

Monitoring and insight: performance and analytics teams who track service behaviour, surface anomalies, and spot patterns

Interpretation and framing: those with service, policy or operational understanding who can make sense of what’s changing, why it matters, and what trade-offs are involved

Coordination and communication: people responsible for aligning decisions across different teams or domains (e.g. service owners, product leads, programme managers)

Change implementation: the delivery and operational teams who adapt systems, processes, and ways of working in practice

🧭 Example:

A spike in failed ID checks is flagged by a performance analyst. A content designer and operations lead discover a recent update to the guidance removed key clarifying information. The change is reversed quickly, and a lightweight test is added to catch similar issues before rollout next time.

Gathering Around What Matters

Calling out relevant teams isn’t about reinforcing silos. It’s about revealing how different parts of the system interact, and who needs to be part of making it better.

Yes, large service organisations often work in handoffs. But that makes a shared picture even more essential. These questions aren’t a reporting framework. They’re a tool for shared inquiry - a way to collectively surface how a service really works, before deciding how to change it.

They can be used to:

Make decisions about where and how to intervene

Set meaningful indicators, not just KPIs by default

Identify misalignments, like tools that don’t match tasks, or policies unaware of operational reality

Bring the right people in, such as frontline staff using a new system, or analysts who need to understand what their data powers

Good service delivery doesn’t begin or end with a programme.

It’s ongoing, adaptive, and cross-cutting.

Service health gives us a way to see public service delivery in terms of purpose, people, and interdependence, not just outputs and ownership.

Start with what’s real.

Bring people around it.

Then decide what to do next.

—

Special thanks to my colleague Francis Bacon at Public Digital with whom I’ve worked with on this topic and whose brilliant thinking on many aspects of technical, delivery and experience health inspired me to round this up.