Bring Clarity to Complex Services (Without Service Mapping)

When mapping isn’t the right starting point, these five interventions help teams see their service clearly and move toward shared outcomes.

A service lens helps with the join-up complex services: getting policy, operations, digital and frontline teams to see the same service, work toward the same outcomes, and make decisions that reinforce rather than dilute each other.

The artefact most people associate with “seeing a service” is the service map: a left-to-right view of steps, roles, systems and decisions, revealing the landscape from both a user and provider perspective.

I’ve done this countless times. While mapping can be a hugely valuable process and artefact, it’s not always the right starting point.

Mapping is less effective when:

it challenges too deeply how the organisation currently understands itself

there are already many maps and yours risks becoming one more

there’s no time or permission to make something comprehensive enough to land well

it’s not yet clear who the map is for or what decisions it will support

it becomes a political artefact rather than a tool for clarity

the service is too fluid or fragmented to stabilise into a single, neat picture

Sometimes the work needs to start elsewhere. Especially when people struggle to explain what the service actually is, what the product actually does, what good looks like, or what evidence they’re using to make decisions.

Here are some examples of non-mapping interventions I’ve used to help give shape to services to make them easier to see and steer.

1. Making a Service Tangible and Recognisable

Most organisations have an internal view of what they do. Ask what service they provide and you’ll hear about the org chart, who sits where and what they do.

When enough parts of an organisation struggle to see what they do as a service, I start by making it tangible using what people already know and naming it in one place.

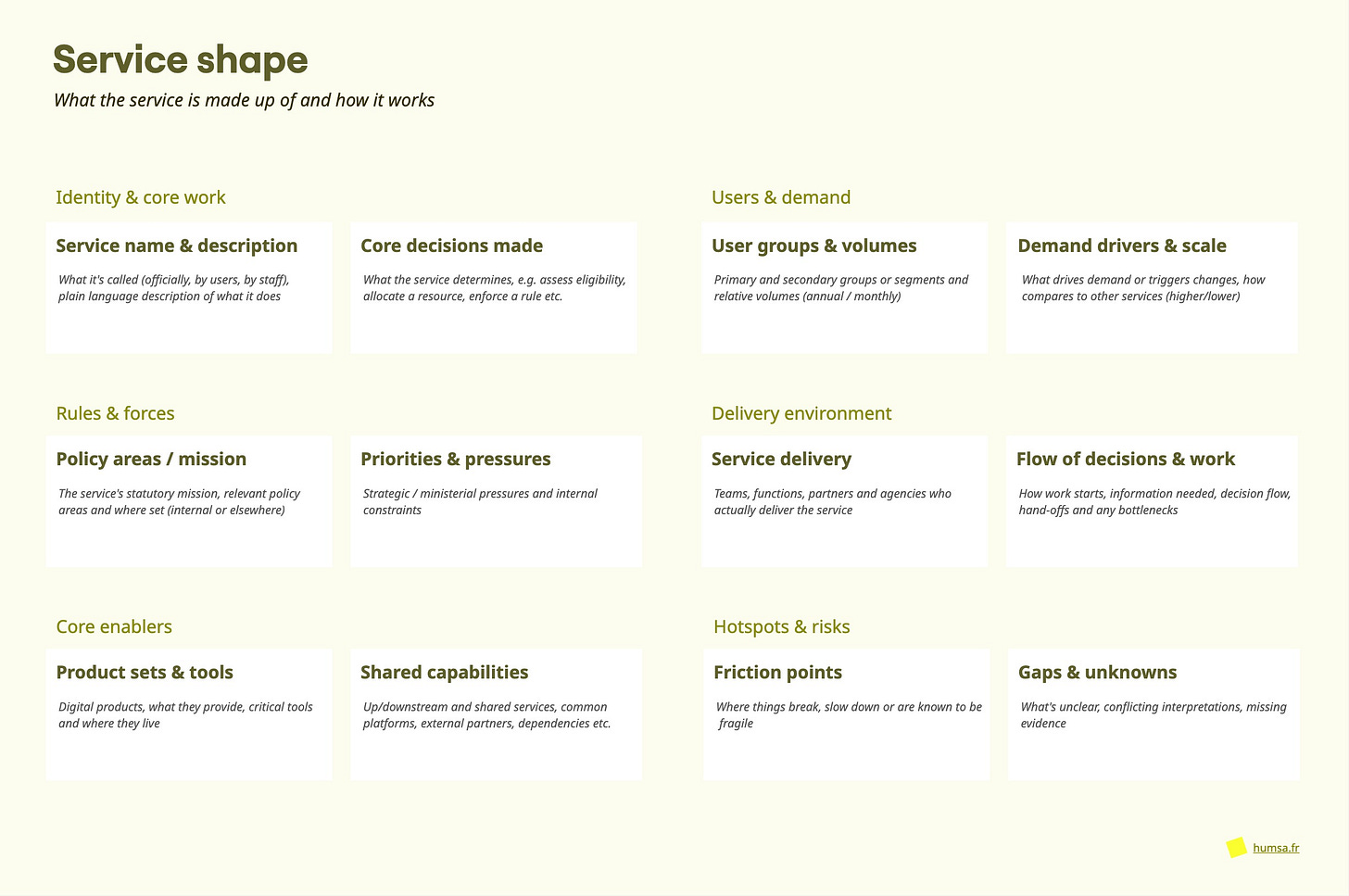

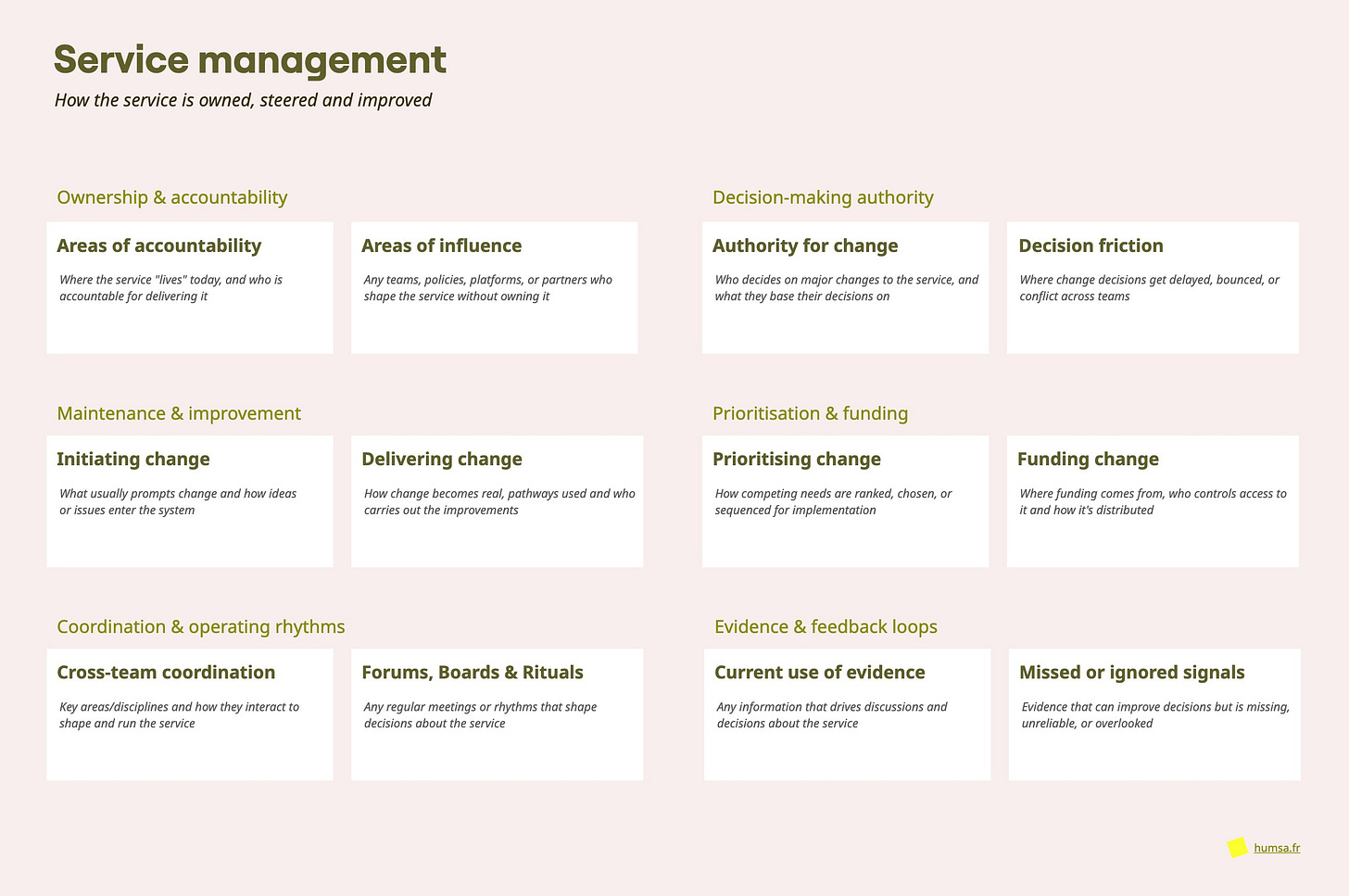

This often takes the form of a simple canvas, made up of a small number of attributes that describe what the service consists of and how it actually runs. For example:

service user groups and volumes

decisions made by the service

ownership and accountability

product or capabilities used

how change is initiated

Here are some example characteristics to mix and match.

I wouldn’t tackle more than six attributes in a short workshop. If they can be identified clearly, a second round can “unflatten” the view by scoring confidence, clarity, level of control etc.

How it helps:

It lets people describe the service context in a non-hierarchical way. Seeing these parts as ‘belonging’ to one service can then help transition to a more outside-in view.

2. A Product Vision That Enables Service Delivery

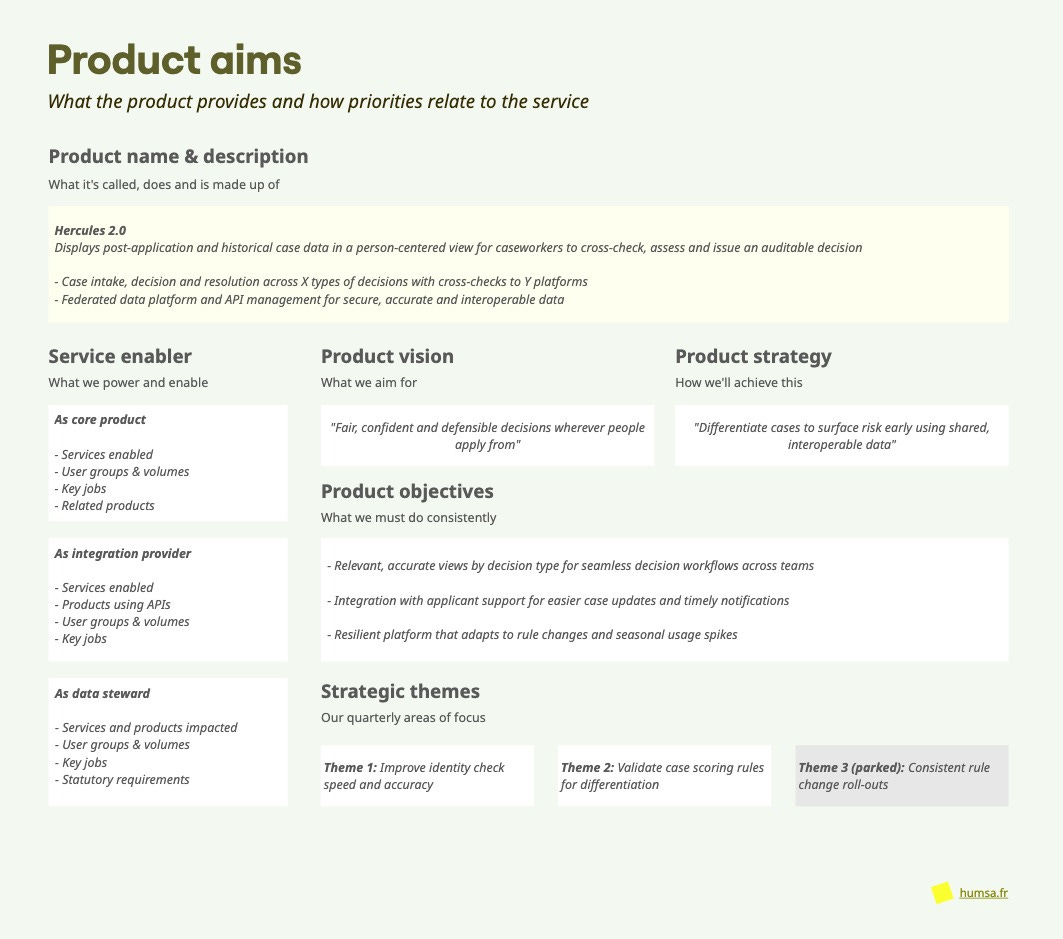

Products and services often get blurred together, especially where service delivery depends on a core product that may support multiple services, alongside service-specific tools and upstream checks or screening systems.

Progress from digital teams is usually visible through Jira backlogs, burndowns and delivery risk. What’s much harder to see is whether this progress is taking the organisation closer to its service or policy goals.

What’s often missing is a middle layer: direction for product teams, clarity for service operators. Many organisations tolerate this ambiguity and chalk it up to professional differences.

To make this understandable, I work with teams to break down:

a product vision and strategy, as in the shift the product enables and how it will get there

the services and user groups impacted and the role the product plays in each

product-level objectives that make explicit what the product is accountable for improving

the job the product actually does, distinguishing for example between automated checks and decision flows

Here’s an example canvas:

We can define what ‘differentiate’ and ‘fair’ mean tangibly in different services and reflect service outcomes. Strategic themes can be used to organise roadmaps and check work in progress against.

Using plain, measurable language helps clarify the product/service boundary: products deliver capabilities; services deliver outcomes.

How it helps:

Once people can explain what the product really does, they can see how it interacts with the service, along with any gaps or misplaced expectations.

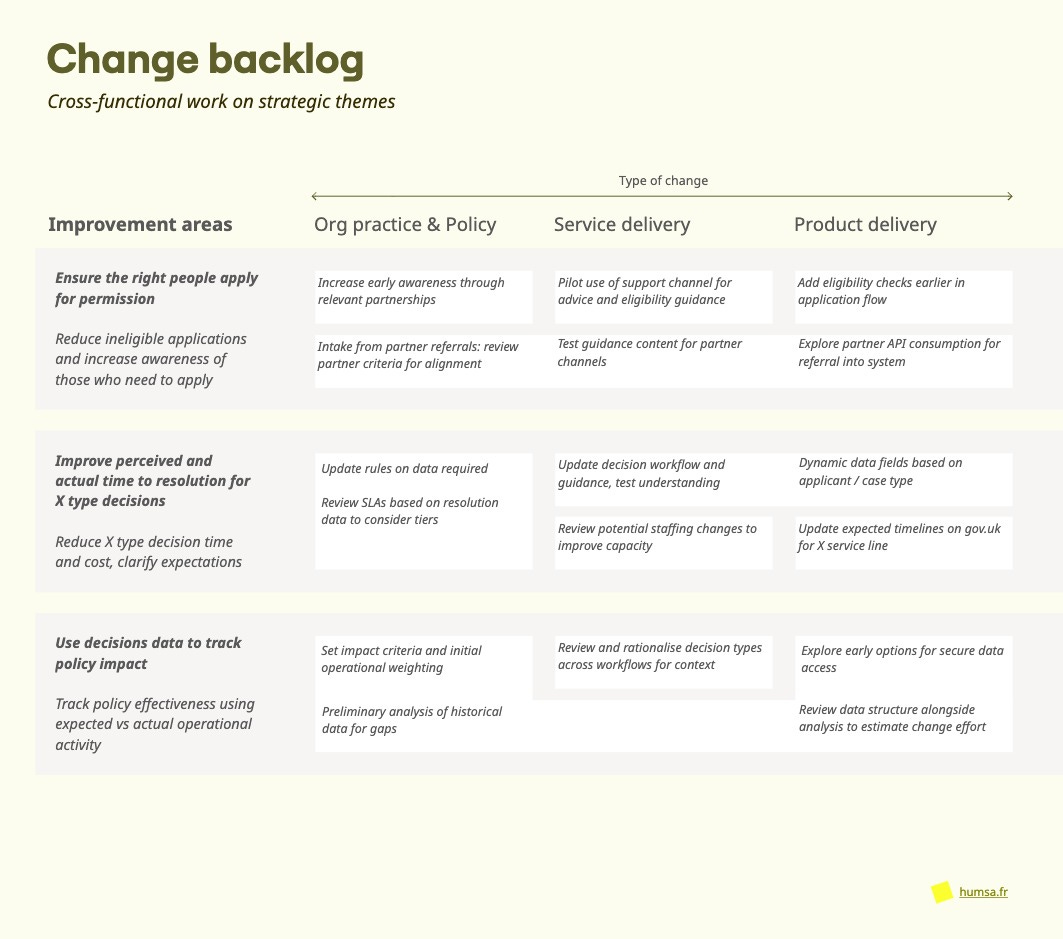

3. A Shared Change Backlog Across Policy, Service & Product

A shared backlog is a way of working toward shared outcomes, even when teams quite rightly operate with different delivery shapes.

Most of us know what misalignment feels like: teams waiting on each other, workarounds emerging, or different areas competing to get “their” change prioritised.

One way to make this more coherent is to map improvement themes across areas of elaboration and delivery. Themes might come from service pain points, strategic shifts, or operational pressures and break down into:

Policy and organisational approach - changes to rules and organisational practices

Service delivery - changes to how the service is run

Related products - changes to products, tooling or data

Some themes can be taken forward independently; others need sequencing or coordination. For example:

The aim isn’t to create a master plan or replace existing backlogs, but to support better conversations: what we’re aiming for, what needs doing by whom, and where join-up matters.

How it helps:

An alternative to Transformation vs BAU or rigid ownership boundaries, making change visible at a level that supports coordination.

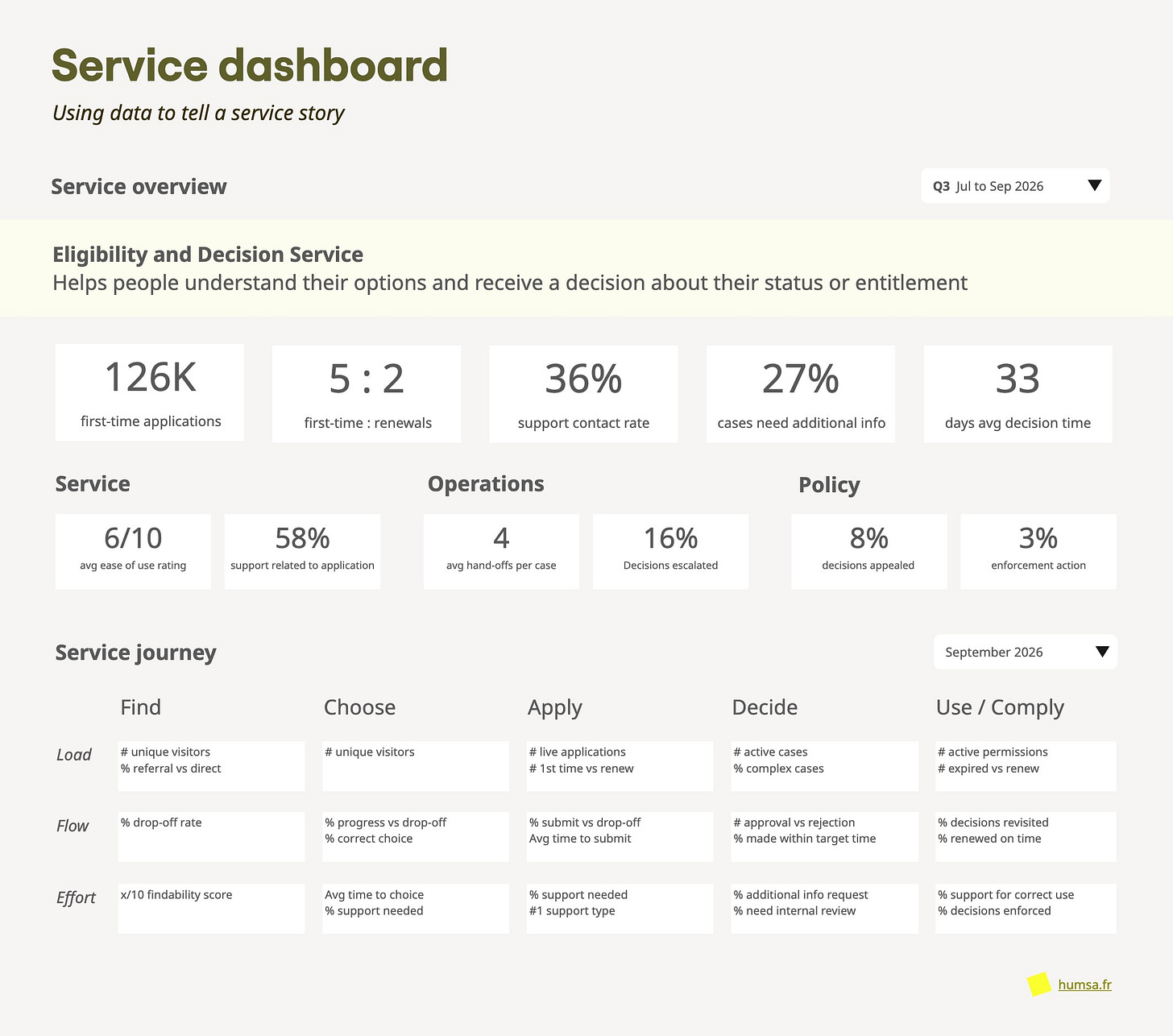

4. Mocking Up a Service Dashboard

I sometimes mock up service dashboards using existing reporting data. Less to measure actual performance, more to tell a story about the service and prompt better decisions.

I choose a few signals that say something about:

how much work the service is doing

what it is trying to achieve

how easy or hard it is to make good decisions

I group signals by intent rather than by team, bringing together indicators that speak to:

the service experience

operational reality

policy aims

I’m particularly interested in decision effort and ease: where the system makes it harder than it needs to be to do the right thing, and where staff need better support, clearer rules, or better tools.

Used this way, a dashboard becomes a shared sense-making tool. It shifts the conversation from reporting to service responsiveness, and naturally raises the question of what outcomes the service is actually working towards.

Why it helps:

To helps people imagine who the audience is - leaders, service owners, policy teams, operational leads - and the kinds of decisions they’re trying to make on a regular basis.

(I’m keen to go deeper than prototyping here; if data or performance folks want to explore this kind of work, I’d love to talk.)

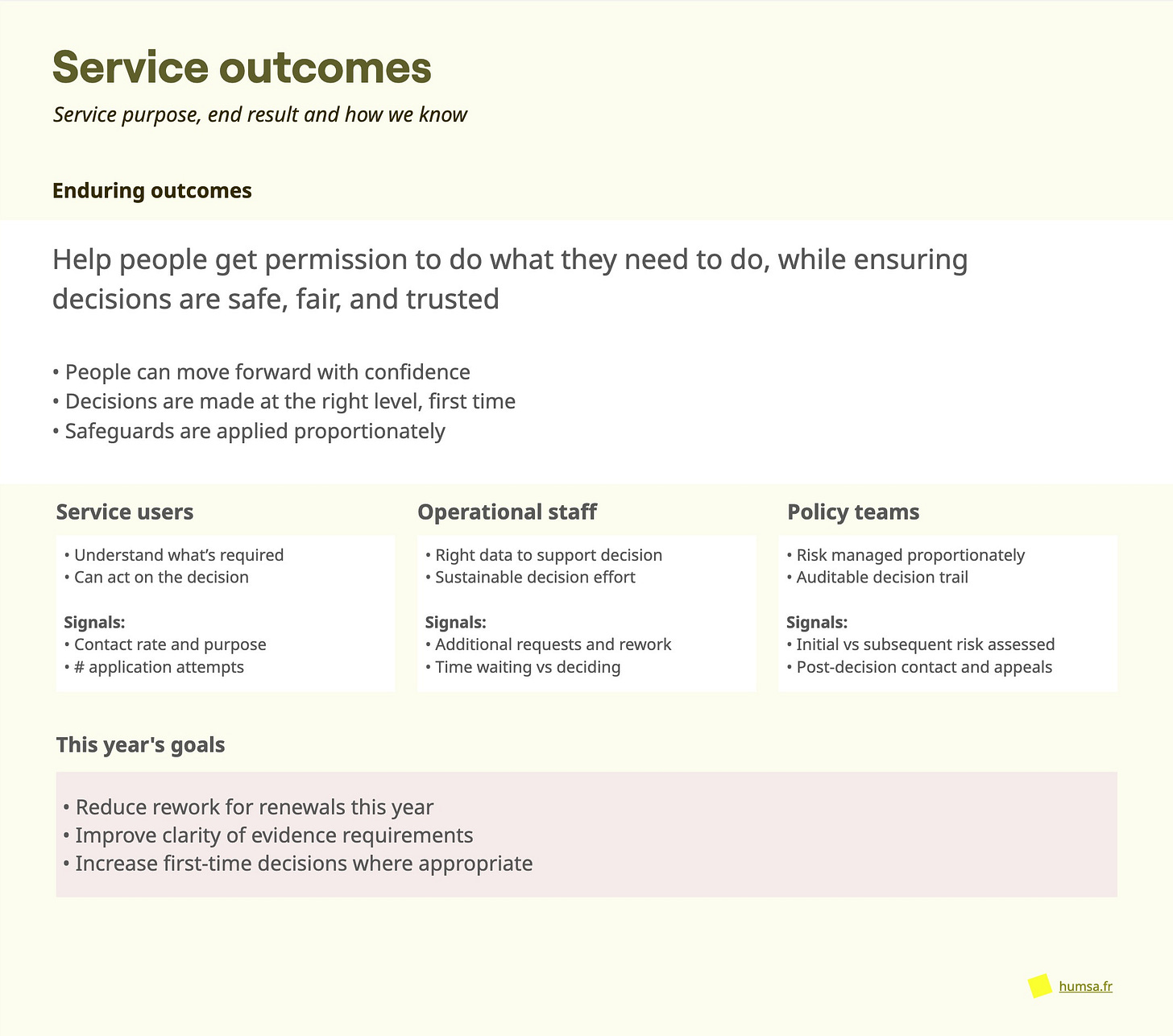

5. Defining Service Outcomes & Measures

In theory this should come first. In practice, it lands better once there’s some shared sense of the service shape and its constraints.

This is a familiar and foundational intervention that Kate Tarling has articulated beautifully. Defining service outcomes is really about naming the service and its purpose: something that’s often assumed, contested, or disagreed on (whether openly or not).

You feel this tension as soon as you try to define outcome that:

people using the service would recognise

teams across policy, service, and product can align to

makes it obvious what “good” looks like

Rather than waiting for the perfect wording, I start with a deliberately imperfect draft - close-ish, provocative and slightly wrong - to surface assumptions early. Agreement emerges slowly through iteration.

In practice, this usually involves:

a clear name for the service

a purpose statement using measurable verbs (assess, decide, support)

a small set of timeless service outcomes, such as:

people receive decisions they can understand and trust

decisions are made at the right level, first time

the service responds proportionately to risk and complexity

These outcomes can then be expressed across perspectives:

user outcomes - “apply once, understand what happens next”

policy outcomes - “intent applied consistently, discretion used transparently”

operational outcomes - “confident decisions with minimal rework”

They’re intentionally timeless and enduring, about the end result rather than the form the service currently takes.

This also makes it possible to define signals rather than fixed KPIs, i.e. what would change if things were improving - faster, easier, more confident, fewer revisits - and what data might indicate that.

Time-bound targets can then sit underneath these outcomes, supporting improvement without redefining success.

Setting outcomes upfront can sometimes be hard. People feel pressure to find exactly the right words, or try to cover everything the service appears to do without being clear on the scope.

The other interventions I’ve shared are all expressions of these outcomes, but they can also catalyse their definition if you’re a bit stuck.

Why it helps:

Service outcomes become the anchor definition of “good:” aligning disciplines, focusing measurement on what matters, and helping organisations move from activity to impact.

While any of these interventions can be ramped up as part of a change programme, none of them necessarily require new teams or big initiatives.

They’re shifts that create clarity and momentum before, during or after a “transformation.” They’re also practical ways of getting to service outcomes in more familiar, immediately useful forms.

In short:

If people can’t clearly describe what the service is

→ Make the service tangible and recognisableIf product teams are delivering but impact feels unclear

→ Clarify the product’s job in relation to the serviceIf change efforts keep tripping over each other

→ Use a shared backlog to align policy, service and product workIf data exists but isn’t helping decisions

→ Prototype a service dashboard to tell the service storyIf “good” is assumed but not shared

→ Draft and refine service outcomes and measures

You don’t need to do these all at once, start with one and return to service outcomes as you go.

This work inevitably surfaces a deeper cultural question: do shared views and outcomes exist to shut down conversation, or to support better ones? Are they instructions, or working agreements?

Clarity is a continuous practice, not a destination. That’s what these approaches are meant to support - mapping included. But that’s a post for another time.